A Variegated Fritillary. Photo by author. A Variegated Fritillary. Photo by author. Yesterday I realized that my 9 ½ year old black lab hates to hike. She endures it when she thinks there will be a fetching reward at the end. Not fetching like attractive, but literally fetching...her ball, her river toy, her stuffed beaver, whatever. She prefers there to be water but she is a desert dog born and raised, so “water” is relative and definitely not a requirement. I have thought all these years that she liked to hike, so you can imagine my surprise when yesterday, as we began our daily sojourn, she just stopped, walked slowly to the creek and sat down - ears back and head bowed. She was definitely saying, “I’m not going anywhere.” I think I was fooling myself into thinking she loved hiking because her Husky sister loved it. Rockie (the Husky) passed away last summer. She was my hiking soulmate, and I have just continued to hike with Chinle never really thinking about the fact that her main motivation had been to keep up with her sister and maybe now, she just didn’t feel the need to do it anymore. In fact, it has dawned on me, that Chinle “loves” hiking like Rockie “loved” the water. Rockie would always swim or dip her paws in but I think it was only because she didn’t want to look like a scaredy cat - I mean, really, what dog does? So today, I got up early and, after hiding my hiking shoes in the truck the night before, I slipped out of the house without making eye contact and went for an adventure all by myself. It’s been years since I hiked alone - without another being (human or canine). And I know it’s trite, but I felt just as Henry David Thoreau did when he wrote, “I took a walk in the woods and came out taller than the trees.” Part of that was because I didn’t have an 80 pound dog pulling me the entire 3 miles, so I literally felt taller than I usually do after our jaunts. But I also felt lighter as though my soul had shed some pounds. To be honest, I also started to feel a little lonely. The last time I was on that particular trail I had Rockie with me. But just as I experienced that fleeting friendlessness, a raven arrived and noisily introduced himself. His loud chatter may have been pointless banter, but I convinced myself he was saying something so profound that I should sit down and listen - granted all of that might have been just an excuse to rest my pounding heart and burning lungs ...3000 feet elevation gain in 3 miles at 11,500 feet altitude is, ummmm, steep and the whole damn place is a little short on oxygen if you ask me. I obliged my cardiovascular system and the bird by sitting on a log where I listened to him rant for a good long while. Ever since I was a teenager and a raven saved my life, I have always felt like I should listen to them whenever they present themselves. I was 17 or 18 and hiking in Arches National Park (by myself), and I got turned around in the Fins. The fins are enormous rock structures that stick out of the earth and sit parallel one after the other. Unsurprisingly, they look like fins. They go on for miles and can become rather mazelike if you aren’t paying attention. I had been in them before with no problems, but that day, well, I wasn’t paying attention, and I got a little lost. As I was staving off sheer panic, a raven appeared. He kept moving (hopping really) from rock to rock ahead of me. And to keep myself from freaking out and get my mind off of how awful it would be to die there and how mad my dad would be, I followed him. Sure enough he eventually led me to a place I recognized and here I am, 30 years later...still hiking alone and talking to ravens. But this particular day, I was staying on a very obvious trail, that went up (and I mean up) through mixed-conifer forest that had been set aside as public lands in 1906. I sat thoroughly entertained by the squawking raven and the quaking aspen and felt great gratitude for those who had the foresight to reserve such lands. This particular spot was in the Columbine-Hondo Wilderness of the Carson National Forest. In 1906, the national forest was designated and in 2014, the wilderness area was designated. The fact that the span of people who found this exact spot to be inspiring enough to save stretched across more than a century is noteworthy. Few places have such holding power. The 20th century saw vast shifts in cultural values and political realities and yet...Americans in 2 different millennia agreed that that place was something special. The Carson National Forest, named after the controversial explorer and map-maker Kit Carson, would come to encompass 1.5 million acres. The Columbine-Hondo Wilderness (which gives even greater protection to part of the area) is 46,000 acres. I am a huge proponent of public lands. Much of that forest would be cordoned off from my enjoyment if it had been left as private lands over this last 110 years. We can suspect the trees might be gone and the habitats more destroyed than they are. So for that I'm grateful. But I am also keenly aware that that place has been sacred long before anyone in modern America deemed it as such, and, in reality, the land upon which I sat truly belongs to the Taos Pueblo. I had just finished a really terrific book by Theodore Catton on the national forests and American Indians and as the raven droned on, I admit I stopped listening as my mind turned toward one of the more interesting stories of this politicized forest from the 20th century. (1) The long and sordid struggle for access to Taos Blue Lake, like the protection impulse for Carson National Forest, spans nearly the entire length of the 20th century. The Taos Puebloans’ historic use of the lake and the surrounding forest lands was debated and denied for nearly 60 years. It became a topic of controversy because of the American government’s decision to include Blue Lake as part of the National Forest in 1906, thereby removing it from the “exclusive use” of any one person or group. The lake (and the surrounding forest) is a sacred space to the Puebloans. They have used it for millennia for religious observances (it’s more profound than that, but blogs are supposed to be short!). In the 20th century, as more and more Americans struggled to make sense of their own needs for wildness, resources, and access, the Puebloans’ claim to the land became a source of conflict and, of course, politics. The 1920s-60s saw the Forest Service mostly reject the Pueblo’s claims to be able to access and protect the lake from the “multiple uses” that were part of the Forest Service’s mandate. John Collier, the head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs under Franklin Roosevelt in the 1930s and a few others advocated for the Taos Pueblo to have access to the area around Blue Lake and to limit other uses (such as cattle ranching that might pollute the lake). Co-management between the service and the Puebloan government was hinted at at one point, and the federal government even tried to “compensate” the Puebloans for the stolen lake. Long story short, the gist of the bureaucratic struggle was that Congress and the various heads of the Department of Agriculture (where, interestingly, the Forest Service is housed) refused to reserve the Blue Lake region for the Puebloans’ exclusive use (despite centuries of colonial governments acknowledging, legally, the Puebloan lands - Spanish, Mexican, and the US government under Abraham Lincoln had all recognized the Taos Pueblo rights to and grants of land and water - of course, we can argue the fact that the Spanish had no right to “grant” the Puebloans anything since it was the Pueblo’s land to begin with...but that’s a conversation for another time). I’ll skip the legalizing that ensued after 1951, when the Puebloans first took their claim to the Indian Claims Commission (established in 1947 and closed in 1978). Suffice it to say that by 1965, the government had decided that, for the Puebloans to win their claim, would require an Act of Congress (I can almost hear Clinton Anderson, Senator from New Mexico at the time, sniggering at that). But we will skip this 20-year part of the story, because the ending is just too good. In 1970, Richard Nixon (likely keenly aware of the growing militancy of the American Indian movement and wanting to create good press for his administration in an increasingly tense time in the nation) intervened to get Congress to give him a bill to return the lake and substantial acreage to the Taos Pueblo. And they did. Read more about how the Puebloans gained the president’s attention here if you are interested. Nixon signed the law commenting that “This is a bill that represents justice, because in 1906 an injustice was done in which land involved in this bill, 48,000 acres, was taken from the Indians involved, the Taos Pueblo Indians. And now, after all those years, the Congress of the United States returns that land to whom it belongs.” You should read the bill signing remarks in their entirety (just click the link directly above) because like many things Nixon said, they are strange. The 60-year Blue Lake saga and the Puebloans’ victory was precedent setting. There are many of these kinds of stories about the history of conflict on public lands in the US - especially the US Forest Service’s management of resources to which so many people lay claim (ranchers, recreationists, indigenous peoples, timber companies, and of course, the mining industry). Those stories and those conflicts are never far from my mind, but on this day, I was feeling grateful for having access to land where I was able to find solace if not exactly total solitude. The boisterous raven had left me, and I was a long way from Blue Lake as I got up from my log and decided it was time to turn around. I mean I could have kept going up to 13,000 feet, of course, but I had a lonely dog at home who needed a river. As I turned down the hill, solitude eluded me once again. This time, in place of the raven, arrived a butterfly - according to a friend of mine who is 14 years old and a butterfly expert, this is a female Variegated Fritillary Euptoieta claudia (see photo). If that’s not right, blame Shaden Higgs. She lives in Bozeman, Montana. The Fritillary stayed with me all the way down the mountain lilting along and alighting just in front of me with every step. I thought about how much more of the world we would all see if we stopped to investigate the spaces around us as often as a butterfly in the woods. In many cultures, including the Taos Puebloan culture, it is believed that butterflies represent renewal and rebirth (there is that re-creation theme again, weird), while others believe butterflies are the spirits of loved ones who have passed and have come back to say hello. Maybe that is why the Fritillary stuck with me for so long, and why I kept having the urge to name her Rockie. I arrived back at the parking area to see a USFS fire truck with a couple of wildland fire scouts standing outside of it. “No fire is there?” I asked casually but really filled with some panic. “Nope,” one replied, “Just keeping our eyes out.” A raven screamed as it dipped precariously close to the firefighters’ heads and then the most gorgeous swallowtail butterfly landed on their truck. The second scout looked at both thoughtfully and said quietly, “Those must be good omens, right? “Absolutely.” I replied, thinking about the immensity of the forest rangers' jobs to protect this land in these dry times and wondering if Blue Lake was a low as other bodies of water in the area. The other scout smiled brightly, “No doubt about it. The ravens have our back and that butterfly is just cool.” Indeed, no doubt about any of that. 1) Theodore Catton, American Indians and National Forests, (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2016). For the Blue Lake story see pp. 93-105.

1 Comment

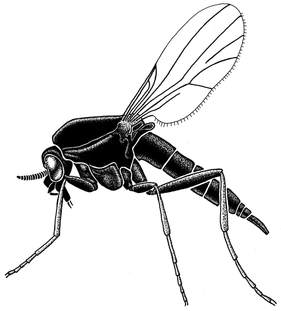

Noseeum, 70 times life size, by Lynn Kimsey. Picture from: Bug Squad: Happenings in the Insect World, University of California Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, May 24, 2013 http://ucanr.edu/blogs/blogcore/postdetail.cfm?postnum=10473 Noseeum, 70 times life size, by Lynn Kimsey. Picture from: Bug Squad: Happenings in the Insect World, University of California Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, May 24, 2013 http://ucanr.edu/blogs/blogcore/postdetail.cfm?postnum=10473 The day was hot - the kind of hot that makes you feel suspicious about the sun’s intention. We headed to the Grand River (the Rio Grande) first. The river is low and I (although not Chinle) can walk across it. Still, it is a scenic river with herons and hawks and geese and ducks keeping us company as we played in the water. On the way to the bank we followed behind a car with a bumper sticker that said “Water is truth.” I grew up around rivers, well, in them really, and I spent the better part of my childhood traipsing around red rock canyons. So I feel most at ease next to muddy currents encased in narrow slots carved into earth for eons. I also wouldn’t know what to do if I wasn’t batting at my ears the whole time we “recreated” in those places. Funny that word, recreated. I’m not a linguist, but Oxford tells me that the word, in this sense, comes from Late Middle English via Old French from Latin recreare “create again, renew.” And I suppose that’s exactly what we are doing when we go for a hike along a stream in a wet forest or a swim in a cold mountain lake. I suspect we are, indeed, seeking truth. But the truth of it is that at times it just sucks...especially during noseeum season. Noseeums are a biting fly. There are a lot of different species but all are from the family Ceratopogonidae. They occur in different names in most places of the world. Even perfect Scotland has them but they are called midges there. Like mosquitos, only the female noseeums bite. And bite they do. They are so tiny you can’t see em coming (see what the name did there? ucannoseethem). I once heard from an old park ranger naturalist friend of mine that they are particularly interested in your head in the desert Southwest because that is where you are sweating and they are seeking moisture. I know they love my eyes and just behind my ears. So anecdotally he must be right, although I’ve never verified that with an entomologist. Come to think of it, that same ranger once told me that rattlesnakes avoided him because he was so mean...so the source may not be all that reliable. So what is the purpose of the noseeum...what, in heaven’s name do they do? Noseeums, from what I can tell, are put on earth to test our resolve to recreate. As they fly close to your ear, they ask the question, over and over and over again, “how much do you really want to be here?” As a youngster we did all sorts of crazy things to keep them away. We wore nets over our heads (it was the 80s, so we were probably close to high fashion), we bought stock in Avon’s Skin So Soft because traditional repellents like Off acted more as bait for the little SOBs. As a little kid I imagined them licking the Off off my skin like a lollypop. Skin so Soft is sort of oily and we were moderately into sun protection, so we lathered on Coppertone SPF 10. At the end of a long day of fun, you can picture us, two oily substances mixed with a bit of sand, dozens of dead noseeums that look from a distance like specks of pepper or very small freckles, and a lot sweat. Anyway...what is the purpose of noseeums? They all reproduce - by drinking blood of course. Some of them pollinate (plants like cacao). Some spread disease. But all of them push you to your existential edge demanding that you ask “why am I here?” They dare you to privilege spiritual renewal over bodily comfort and then they verily laugh at your feeble attempts to assert your existence beyond them. After a couple of hours of swatting and splashing, Chinle and I decided it was time for a nap and a beer. After our rest, we wandered to one of our favorite watering holes (after a couple of beers, that bumper sticker about truth begins to make so much more sense). Playing at the Mothership (yep, that’s its name) there was the local band (I’m not making this up), the NoSeeUms. They define themselves as as a “groove-grass” band, an eclectic mix of funky, progressive Americana and their slogan is “You’ll See Em!” Clever right? And like the fly, they sort of zip in and out of your consciousness as they play. I sat listening, contemplating, and smiling as I scratched the dozen or so tiny bites littered across my scalp. An aging hippie looked at me and gestured toward my scratching, “noseeums got you?” I hid my surprise and and said wryly, “yes, and the bugs are pretty potent too.” He laughed and got up to go dance, swaying to the music and, I suspect, renewing his spirit as the Noseeums played on.  I was beating myself up about not writing more consistently...fearful that people would give up on the blog and stop reading and then I realized very few are reading it anyway! ha! I also have to figure out a way to write for me and stop worrying about deadlines or audience. My writing life has always been about deadlines...writing political missives for the Governor’s Office in Colorado in the 90s, grad school in the 00s, the publishing process with Emily Wakild most recently (our book is OUT -- which is very exciting! Check it out here! - you can also buy it from Amazon.com). No matter what or where I was writing, it has been largely for someone else. With an audience and a deadline in mind. And I think the next step in my process in become an actual writer is to write everyday (or darn near) for me! So I’ve decided that maybe my public writing (the blog) is a summer blog. It’s in the summer, after classes and coaching have ended, that my spirit and my mind have the creative capacity to see the world. So here is the first of what I hope will be several entries this summer. The vet’s eyes have the glaze of age. He sits staring at my dog with sympathy and slight annoyance. “The nettles are especially bad this year. So my guess is she got into some of those.” I then suspect the annoyance is at the nettles not at my dog. I look hopefully at him as a drip of sweat trickles down my back. I have as few clothes on as is permissible even in this hippie, “you do you” town, and I’m still panting from the suffocating heat in the tiny room where my dog’s drool puddles around my feet. “So….” I say expectedly. “Are nettles fatal? I mean, she couldn’t have eaten many. I watched her the whole time.” He looks at me with pity and with wisdom. “It’s been my experience their life is rough for a day or 2 and then they come out of it. Oh and you can’t have watched her the whole time.” He then turns to Ed and tells him to lift my 80 pound lab/Weimruner mix up onto a 5 foot high examining table. The table, I think to myself, is almost as tall as my vet back home . Ed is the 300 pound vet tech who greeted me at the door with his outstretched hand attached to arm littered with skull tattoos. Neither he nor the vet introduced themselves. They didn’t ask my name - only Chinle’s. Which I guess is the only important name to know in the big scheme of things. Chinle and I are in Taos, New Mexico for our summer getaway. We come every year. This year it is 95 degrees out (highs are usually around 75 - when it’s 80 the locals are freaking out). The plants are all withered, some haven’t leafed out, except, apparently, the nettles. The creek (where the nettles were to be found) was lower than ever and wildfires nipped at the boundaries of this mountain valley threatening the lifeblood of the region (if there is anything ranchers, mule deer, and mountain bike shops owners agree on, it’s that wildfire is bad for business). There is nothing worse than being away from your amazing Southeast Asian Hindu vet (who is Gaia personified) when your pup is in distress. Dr. Darwalla (at Bernarda Vet Hospital) is about 5 feet tall. Her office has no examining tables. Instead the animals get to lie on comfy pads with hygienic covers, and the humans have big comfy chairs. All of her staff is female and there is aromatherapy to calm nerves (human and non). Our favorite tech is Cristina, a thin Chicana who exudes a no nonsense compassion. Chinle loves them all. As I walk into the cramped waiting room with the tall, metal examining table and a folding metal chair, I thought to myself “we aren’t in Tucson anymore.” The room was likely 90 degrees (maybe that’s an exaggeration, but it was cramped, 95 outside and there is no AC anywhere in this mountain town). I’m pretty sure Chinle and I both suspected we were going to die...she didn’t say so and neither did I, but I think we both thought it. We waited for 30 minutes, but I couldn’t annoyed. They squeezed us in - so desperate and, relatively helpless we sat wishing Dr. D wasn’t a hard 10 hour drive away. The vet, who I hear Ed call “Dr. Ted,” says to me, “it’s the dry year. Only the gnarliest things survive weather like this.” I ask him if this is unusual. I’ve never experienced it but we usually come in July...so maybe I don’t know June. He looks at me with an unperturbed patience. “Nope. Not normal. Had a rancher call me on Monday with a cow who had heat exhaustion. That’s a first.” Ed, meanwhile, is grunting at Chinle who refuses to lay down on the table….he says “you can either do it on your own or I’m gonna do it for you.” One time Dr. D sent us home because she didn’t think the dog was in the right emotional state to be examined, and she didn’t want to hurt her. I winced and started to say something and then remembered that Ed was 300 lb and definitely in control, so instead I sat expectedly waiting for the “we need to take xrays, do blood work, and that will be $300” spiel. Instead, Dr. Ted left the room and came back with 2 syringes. “One of these will stop the drooling, one is benadryl. Feed her as much as she will eat. And if you have trouble in the night, call me.” In went the medicine and out went Dr. Ted. Not a goodbye, not a “nice meeting you,” just a small smile a slow shuffle. Ed looked at me and I said, “well, I think I’ll go drink a beer or 10 and watch my dog drool.” He smiled for the first time and said, “Chinle is a cool dog. Named for Chinle, Arizona?” No one EVER knows that. “Yeah, I said. “Sorta. Named for the Chinle formation on the Colorado Plateau.” Ed explained he had worked at a truck stop in Gallup for a time - might explain the skull tattoos I thought. “I’ll drink a beer or 10 for ya. She’s gonna be ok.” I checked out - credit card in hand ready for the $300 charge. $80, a smile, a shuffle, and a subtle reassurance from gruff men who were, despite all appearances to the contrary, as tender as the tiny Hindu back home. Definitely not in Tucson anymore. But turns out that that’s perfectly ok. |

Archives

July 2020

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed